Attention is all we have

A conjectural theory of cognitive inequality

Some people are smarter than others—and some are fabulously smart. We may disagree on many things, but can we at least agree on that?

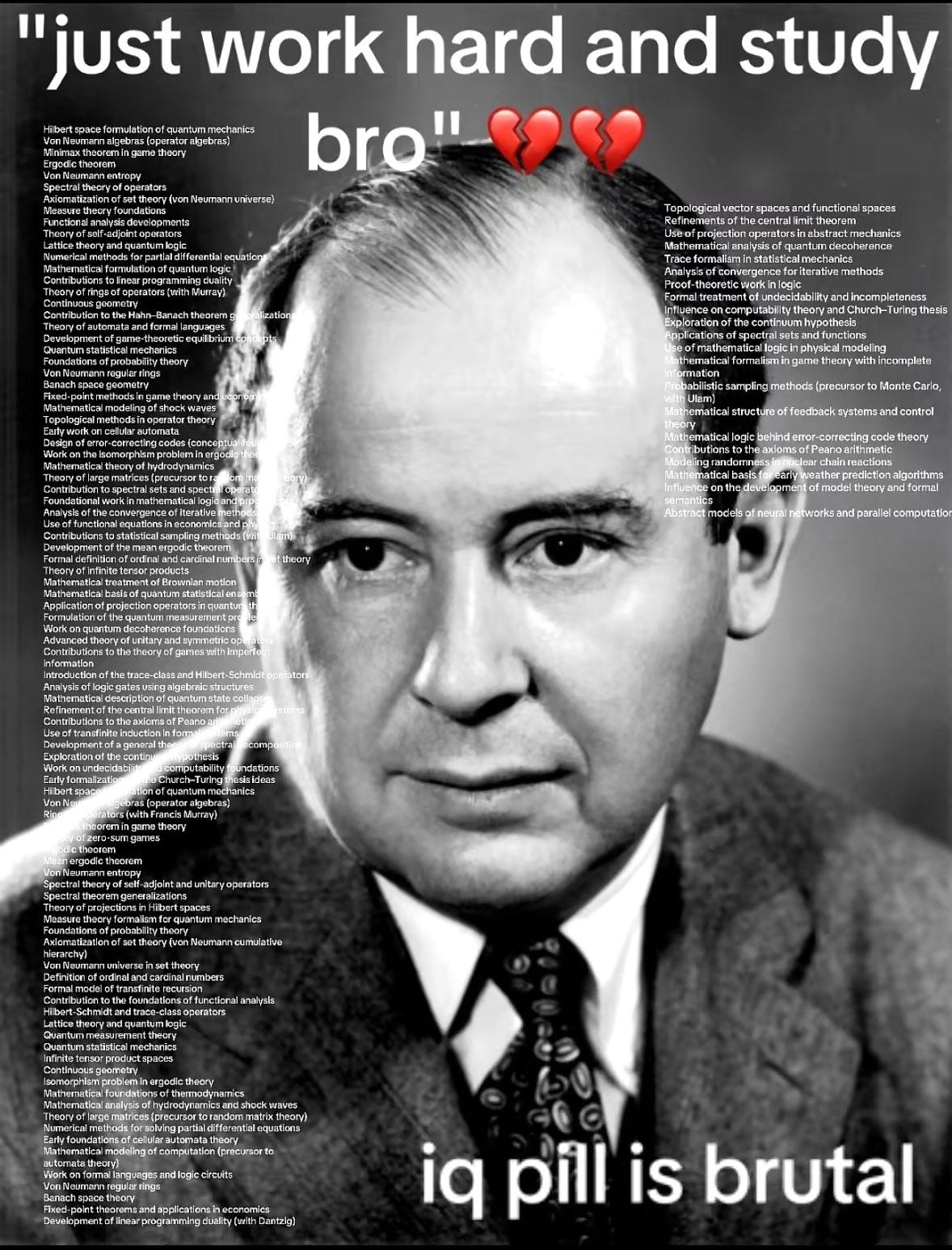

The origin of cognitive inequality is a hot, divisive topic. The existence of cognitive inequality is hardly controversial. We do struggle to come up with a satisfactory definition of intelligence, especially in its most creative and socially valuable forms, but most agree that people like Leonardo da Vinci, William Shakespeare, Nikola Tesla, or John von Neumann were extraordinarily intelligent.

This aligns well with my experience in pure math academia, where careers and even personal identities are shaped by the shared perception of a mesmerizingly wide cognitive gap between mathematicians. This is a central theme in their discussions and a source of both fear and admiration.

Yet for all the culture wars on the origins of cognitive inequality, there is little debate on its very nature.

When someone is unusually smart, what is going on in their brain? This is a different question from “where does cognitive inequality come from?”, and also from “can we really measure it?” (another controversial topic).

It is a basic, foundational question that stems from two widely accepted facts—that some people are smarter than others, and that intelligence is a manifestation of brain activity—and asks for the natural follow-up: what is really going on? What are the physical differences between the brain of a super smart person and the brain of a normal person?

The garden of bad metaphors

Despite its adjacency to some of the most contentious issues in science, this topic has remained relatively quiet. It might be because of this very proximity.

Or maybe the question is too simple and natural. Five-year olds love to ask brutal questions like this one, but grown-ups are usually more hesitant, as they don’t want to come across as unsophisticated.

Or perhaps this is because there were historical precedents where people went looking for answers and came back empty-handed. The brain of Carl Friedrich Gauss sits in a jar on a storage shelf somewhere at the University of Göttingen, and is so unremarkable that it remained mislabeled for over a century without anyone noticing. After Albert Einstein died in 1955, the pathologist removed his brain without the permission of the family, preserved it in formaldehyde, and dissected it into hundreds of slices—some researchers claimed to have observed peculiarities in the samples, but these findings are generally regarded as unconvincing.

If we stick to solid science, there is remarkably little we know on the subject.

But here’s the catch. While the simplest and most natural question remains unaddressed, people continue to rely on the same flawed brain metaphors and the same dubious biological assumptions. This only adds to the confusion around IQ and the heritability of intelligence.

For example, people marvel at the “speed” and “working memory” of von Neumann’s brain, as if it were a CPU with a unique clock speed and L1 cache. But from a biochemical perspective, what could this even mean?

Genes code for proteins, which assemble into cells, which assemble into tissues. Within-species genetic variability isn’t about new genes coding for new proteins with new functional roles that open the possibility for radically new architectures—it is about minute variations in the quantity and conformation of the same proteins, which retain the same overall structures and functional roles.

It is true that these minute variations compound over embryogenesis and life, resulting in sizable physical and physiological differences between individuals. Yet it is also true that all human beings are built with the same architecture and the same functional blueprint. It’s not like some people have normal hearts while others have 500 horsepower turbopumps. And it’s not like some have Snapdragon 8 smartphone processors in their brains while others have NVIDIA H200 Tensor Core GPUs.

To stick with this terrible CPU metaphor, it’s more like some people have a Snapdragon 7 while others have a Snapdragon 8—the performance gap is noticeable, but everybody runs the same apps.

There is one caveat to that. Genetic anomalies can derail brain development and hamper its normal functioning. A Snapdragon 8 with a defunct thermal management probe will not operate properly. Phenylketonuria, also known as PKU, is an example of a recessive genetic condition that, if untreated, can lead to microcephaly and severe learning disabilities.

By contrast, there is no accidental change to a Snapdragon 8 that magically turns it into an NVIDIA H200. This probably explains why we have never found any specific mutation that causes a drastic increase in cognitive ability.

Yet, still, there MUST be a physical difference between the brain of a super smart person and that of a normal person. If not, where would the cognitive difference come from?

There are no miracle people

Throughout my journey as a pure mathematician, it often struck me that progress wasn’t only about mathematics itself, but also metacognition and emotion control.

Like many math students, I started out with a strong hereditarian prior, because I couldn’t think of an alternate model for the shocking inequality pattern around me—which, clearly, couldn’t be explained by social determinism.

Then, over time, I realized that genetic determinism was equally problematic, not least because it couldn’t account for my own progress trajectory.

Later on, I found out that many prominent mathematicians had tried to articulate the idea that their talent was first and foremost a cognitive attitude. A famous example is that of Descartes who, in the opening lines of his Discourse on Method, insisted that he wasn’t particularly gifted:

For myself, I have never presumed my mind to be any way more accomplished than that of the common man.

Instead, he attributed his successes to his chance discovery of a miraculous “method” that, for all practical matters, is an assortment of metacognitive techniques aimed at improving the clarity and reliability of one’s intuition. If you were to generate a tag cloud of his favorite words, intuition, clear and distinct would stand out with massive fonts. The same themes can be found over and over again in the writings of Poincaré, Hadamard, Thurston, Grothendieck, and many others.

This is part of a broader pattern where some of the biggest names in science have rejected the notion that they were born with unique abilities, insisting instead on their curiosity and stubbornness:

Isaac Newton: “But if I have done the public any service this way it is due to nothing but industry & a patient thought.”

Albert Einstein: “I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious.”

Richard Feynman: “I was an ordinary person who studied hard. There are no miracle people. It just happens they got interested in this thing, and they learnt all this stuff.”

Alexander Grothendieck: “This power is in no way some extraordinary gift—like an uncommon cerebral strength, (shall we say). . . . Such gifts are certainly precious, worthy of the envy of people (like me) who haven’t been blessed with them at birth, ‘beyond measure.’”

Needless to say, these bold declarations have barely made a dent in the hereditarian carapace of the general public.

To be clear, I completely get why most people find these statements absurd and hypocritical. I remember hearing Einstein’s “no special talent” quote when I was fifteen, and instantly hating it. Seriously, who wants to hear supermodels lecturing us on the importance of inner beauty? Then I became a professional mathematician and Einstein’s quote gradually felt less and less irritating. And, after I crossed a certain threshold in my career, it even appeared profound.

If all these brilliant people failed to communicate their point, it might have been because they weren’t explicit enough about what they meant by industry, patient thought, or curiosity.

This is a central theme of my book Mathematica, a Secret World of Intuition and Curiosity, which opens with Einstein’s “no special talent” quote and tries to fill in the missing details—what it means to do math, the unseen actions that we perform in our heads, the slow and gradual build-up of our intuition.

We have no good words to discuss these things. No one ever explained to us what it means to think, meditate, imagine, reason, or dream.

What is the neurological basis of these activities? What do they have in common? What differentiates them? What are their long-term effects on our brains? Could it be that some people practice them the wrong way, while others have stumbled upon remarkably effective techniques that radically transformed their capabilities?

I am a mathematician, not a neuroscientist, and I didn’t get to these questions through theoretical considerations. Rather, I took the practical path of trying to become better at math, experimenting with myself, tinkering with my mental imagery, and doubling down on what worked best.

On the surface, this is just a story about mathematics—and this part is fairly consensual.

Most mathematicians agree on the phenomenology of “doing math”, and they often feel that traditional discourses about mathematics miss or misrepresent something fundamental about their inner experience.

The consensus breaks down when discussing the consequences. Surprisingly, some agree that math talent develops through a specific mental practice that school never really explains, yet stick to the idea that it is primarily innate.

This is where the relatively niche story of extreme mathematical talent collides with the much broader cultural and scientific issue of cognitive inequality.

Mathematics is widely considered to be the purest and most “g-loaded” form of intelligence—the dispute about the actual thought processes of one-in-a-million outlier mathematicians reveals, at its core, a dispute about the fundamentals of human cognition.

This puts us mathematicians in an awkward spot, as our autobiographical knowledge often conflicts with popular hereditarian myths.

I have written on this before (on Turkheimer’s Third Law, on the catastrophic science of Twins Reared Apart) and will continue the series. But debunking bad science is one thing, and explaining math talent is another.

Since I have no expertise on the core neuroscience, I have avoided this topic as much as possible.

However, after seeing the same bad brain metaphors popping up again and again in my social media timelines, I am coming to the conclusion that hereditarian myths are so tightly intertwined with flawed models of human cognition that it is impossible to debunk the former without fixing the latter.

Everyone needs a theory, especially when established science hasn’t yet provided one. If I could move away from my past hereditarian beliefs, it was because I cobbled together my own alternate model of cognitive inequality, informed by my life experience and my (imperfect) understanding of modern neuroscience.

Before I share this private, conjectural theory, and before everyone jumps to the comment section to call out my recklessness, let me clarify its epistemic status:

First, it is nothing but a theory—that is, a coherent set of unproven hypotheses. I have no proof, no empirical evidence, and no legitimacy on the subject.

Second, the theory is clearly simplistic and incomplete. It has gaps, blindspots, ambiguities, some of which are intentional (this is a Substack post, not a peer-reviewed publication) and others result from my ignorance and naivety.

This is just my private attempt to reconcile my own experience of becoming better at math with this fundamental lesson from neuroscience: the brain is a learning device, not a computing device. I am sharing it chiefly because of its value as a mental model.

This theory isn’t perfect, but it is arguably less biologically absurd than “von Neumann was a mutant with a crazy fast CPU.”

A conjectural theory of cognitive inequality

Conjecture 1. Some differences in the structure, volume, speed, and efficiency of neural tissue result from genetic variability, but they cannot account for the magnitude of the observed cognitive inequality.One known issue with IQ is that it artificially compresses the upper end of the distribution to fit a bell curve. Subjectively, the cognitive gap in math (and many other domains) feels much wider than that. Here is how I put it in my book:

Math is so unequal that it’s as if some people could run the one-hundred-meter dash in under a second, while the majority wouldn’t make it in a week. While it’s conceivable that some people may genetically be endowed with a neuronal metabolism that is more efficient and powerful, making them, let’s say, twice as capable in math, or why not ten times as capable in math, it’s hard to believe that genes alone could explain such an absurd level of inequality.

As detailed in an earlier post, the heuristic is that highly heritable polygenic traits are typically Gaussian—the canonical example being height, where people cluster in a narrow ±25% band around the mean—while the distribution of math talent has a much fatter tail, like a Pareto distribution.

The phrasing of the conjecture is intentionally informal, but it can be turned into a quantified, falsifiable prediction:

Consider the population P of one-in-a-million overachievers in the most cognitively demanding fields. You could pick active chess grandmasters, International Math Olympiads gold medallists, Fields medallists & invited speakers at the International Congress of Mathematics, Nobel laureates in physics, or whichever variation you like. There is some subjectivity in these choices, but I suspect most people will find them relevant. My prediction is that we will never find a within-family polygenic score S such that the median value of S on the population P lies in the top centile for S with respect to the general population.

I wouldn’t actually be surprised if P turned out to be indistinguishable from the top decile, but the safest top centile prediction is already substantial: to go from top centile polygenic scores to one-in-a-million outcomes, there would be four orders of magnitude unexplained by genetics.

This falsifiable version has two unfortunate issues: 1/ it relies on achievement as a proxy for talent, 2/ it is elitist. This is because the conjecture is fundamentally about the non-Gaussian aspects of cognitive inequality, which are more readily visible in the tail part of the distribution (a region where there exists no well-calibrated measurement of cognitive talent).

A less explicitly testable but more relatable version would be: if you’re genetically average, you still have a non-trivial chance of landing in the top 1% for any meaningful dimension of cognitive achievement.

The next conjecture is harder to turn into a quantified, falsifiable statement. But it is a natural counterpart to Conjecture 1, since the interconnected structure of our brain is its one aspect that could credibly exhibit extreme, Pareto-like variability.

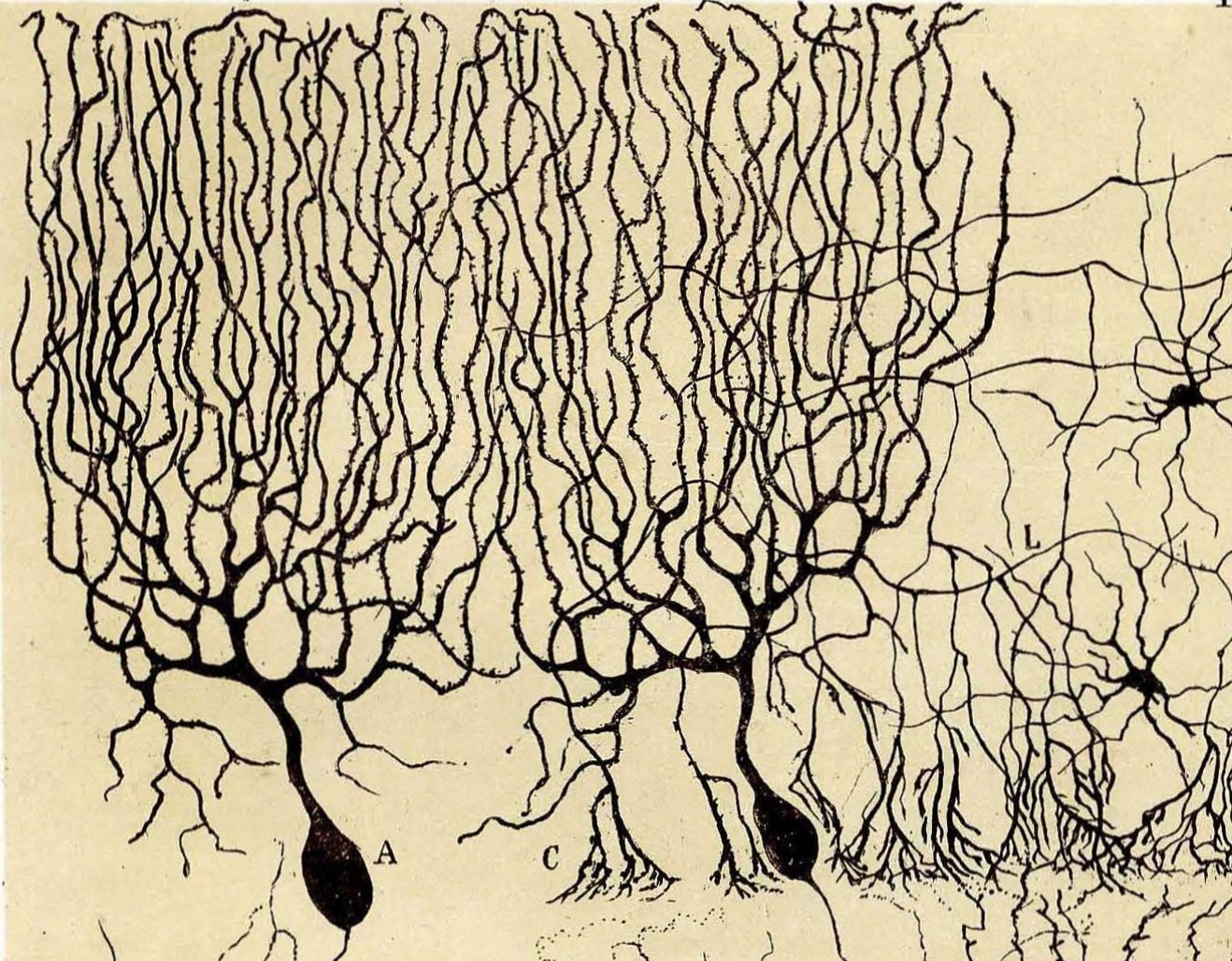

Conjecture 2. At any given moment, the measured cognitive differences between individuals are primarily explained by differences in their synaptic connectomes.This aligns with the conventional view that human intelligence emerges from the interconnected network of neurons. The Parietal-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT)—a classical biological model—explains cognitive inequality by the relative quality of the integration between different regions of the brain, emphasizing the importance of the connectome.

Of course, the human brain has some fixed, heritable features, and its morphogenesis is controlled by regulatory genes that vary from one person to another. But, again, this feels more like Snapdragon 7 vs Snapdragon 8 nuances.

What matters here is that the fine interconnected structure is continuously modified in response to stimuli. In fact, this plasticity is the prevalent explanation for learning and memory formation, as captured by the Synaptic Plasticity and Memory Hypothesis:

Activity-dependent synaptic plasticity is induced at appropriate synapses during memory formation and is both necessary and sufficient for the information storage underlying the type of memory mediated by the brain area in which that plasticity is observed.

The only bit of Conjecture 2 that might be original is its emphasis on measurement. It claims, in particular, that IQ tests primarily measure differences in the connectome.

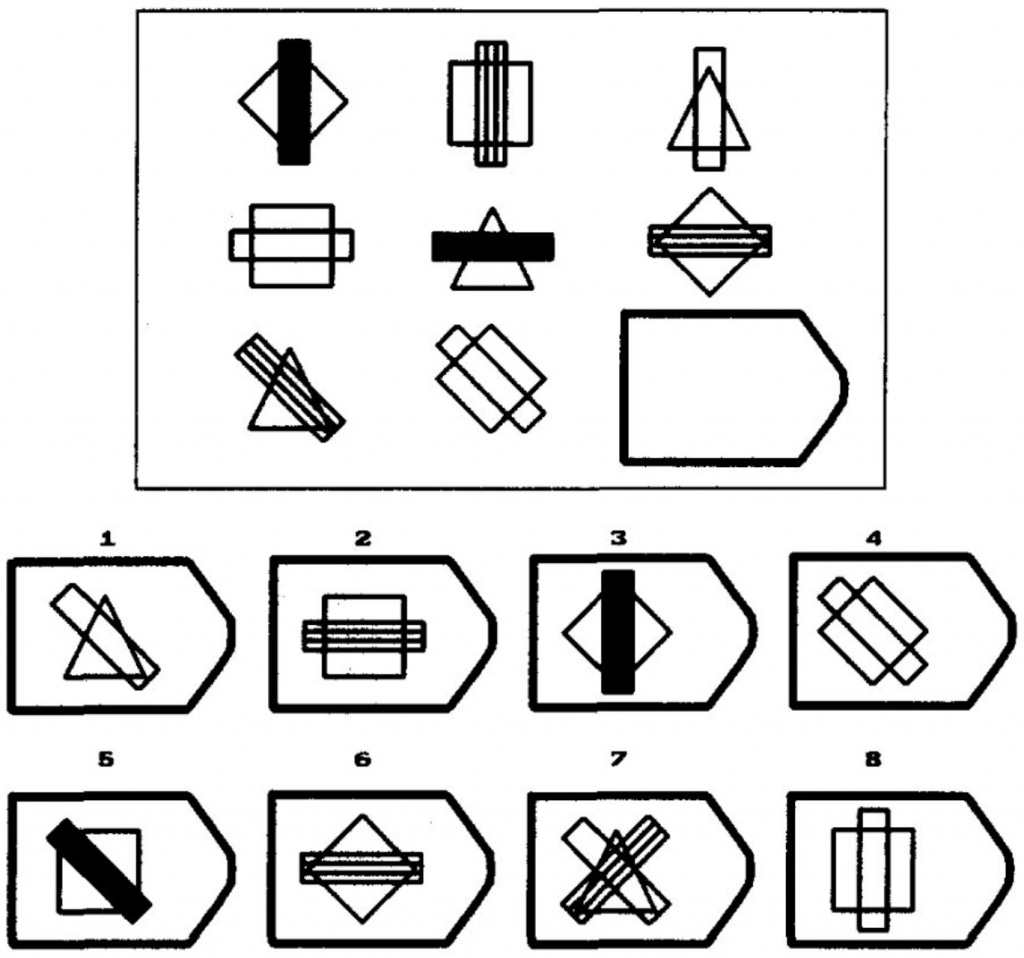

Let me motivate this by sharing my personal reaction to Raven’s Progressive Matrices, one of the most common IQ tests, and supposedly one of the most g-loaded ones. Here’s a typical question:

I have no idea how “normal” people approach a question like this one, but it is very hard for a mathematician like me to take it as a satisfactory test of “working memory,” “processing speed,” or “logical thinking”—whatever these expressions mean.

I hardly have to think to get the right answer. When looking at the picture, I get the eidetic perception of three superimposed permutation matrices (one for the background geometric shape, one for the color of the foreground rectangle, one for the angle of the foreground rectangle.) And, thanks to this eidetic perception, I perceive this question as requiring the same cognitive load as computing 132 + 37.

Subjectively, it feels that by projecting mathematical structure onto the picture, I am able to reduce the need for “working memory”.

Now you could object that I was born with a special brain equipped with eidetic perception of permutation matrices. But I know for a fact that this wasn’t the case. I only learnt about this notion when I was eighteen, and I continued to develop my intuition for it over the following decades, practicing undergraduate linear algebra, then graduate-level group theory, then producing original research on structures that generalize permutations. Over the years, these patterns have become as natural and concrete to me as whole numbers are to laypeople. I feel them like visual rhythms.

While my degree of algebraic synesthesia might be extreme, I suspect that many software engineers—and other professionals who are regularly exposed to tabular structures—develop a similar feel. The increasing penetration of tabular structures in our cognitive environments might actually explain why Raven’s Progressive Matrices “has demonstrated a rate of IQ gain of 7 points per decade, more than double the rate of the Flynn effect as manifested on WAIS, SB, and other multifactorial intellectual tests.”

The Flynn effect applies to all mathematical structures, including the ones that feel obvious to “normal” people. Two thousand years ago, in Ancient Rome, my comparison “trivial” problem (132 + 37 = 169) would have constituted a more challenging IQ test question (CXXXII + XXXVII = CLXIX.)

Our number sense has substantially evolved over the past millennia. We live in a world where (almost) everybody understands Hindu-Arabic numerals, (almost) everybody understands zero, and (almost) everybody understands negative numbers—three notions that had long been out of reach of ordinary people. This large-scale anthropological transformation, which cannot be explained by changes in our genomes, is directly attributable to changes in our cultural and technological environment.

Note that Conjecture 2, in itself, is entirely compatible with the hereditarian worldview. Indeed, it could be that some people are born with substantially better learning mechanisms, producing over time a vastly superior connectome. It could be, for example, that my unusual ability to develop eidetic perceptions of mathematical structures is entirely explained by genetic factors.

However, this will become less credible in light of the next three conjectures.

Conjecture 3. People have vastly different mental habits and metacognitive approaches.This one is very concrete, despite the unfortunate softness of its language. This makes it the most easily testable.

The reason for the soft language is one we already discussed—we have no biologically meaningful words to express the specific unseen actions that we can perform in our heads when we think, meditate, imagine, reason, daydream…

Whenever neuroscientists observe brain activity with EEG or MRI, they notice wildly different activation patterns. This is in fact the very reason why they study brain activity: to see how it varies in reaction to certain stimuli, or from one person to another. Yet, somehow, we lack the cultural scaffolding to take notice of our distinct “brain modes” and train ourselves to use them strategically.

We know about wakefulness and sleep, and within sleep we know about paradoxical sleep—but there are many flavors of wakefulness. Mental habits and metacognitive approaches are my attempts to make up for this missing vocabulary.

The conjecture predicts that, if we make a reasonable effort to categorize these “brain modes” and the distinct strategies one could employ to switch from one to another when accomplishing certain tasks, and if we produce statistics of how much time different people spend on distinct “brain modes” over weeks and months, we will find shocking differences.

Metaphorically, my prediction is that some are walking 100,000 steps a day while others are constantly doomscrolling on their sofas.

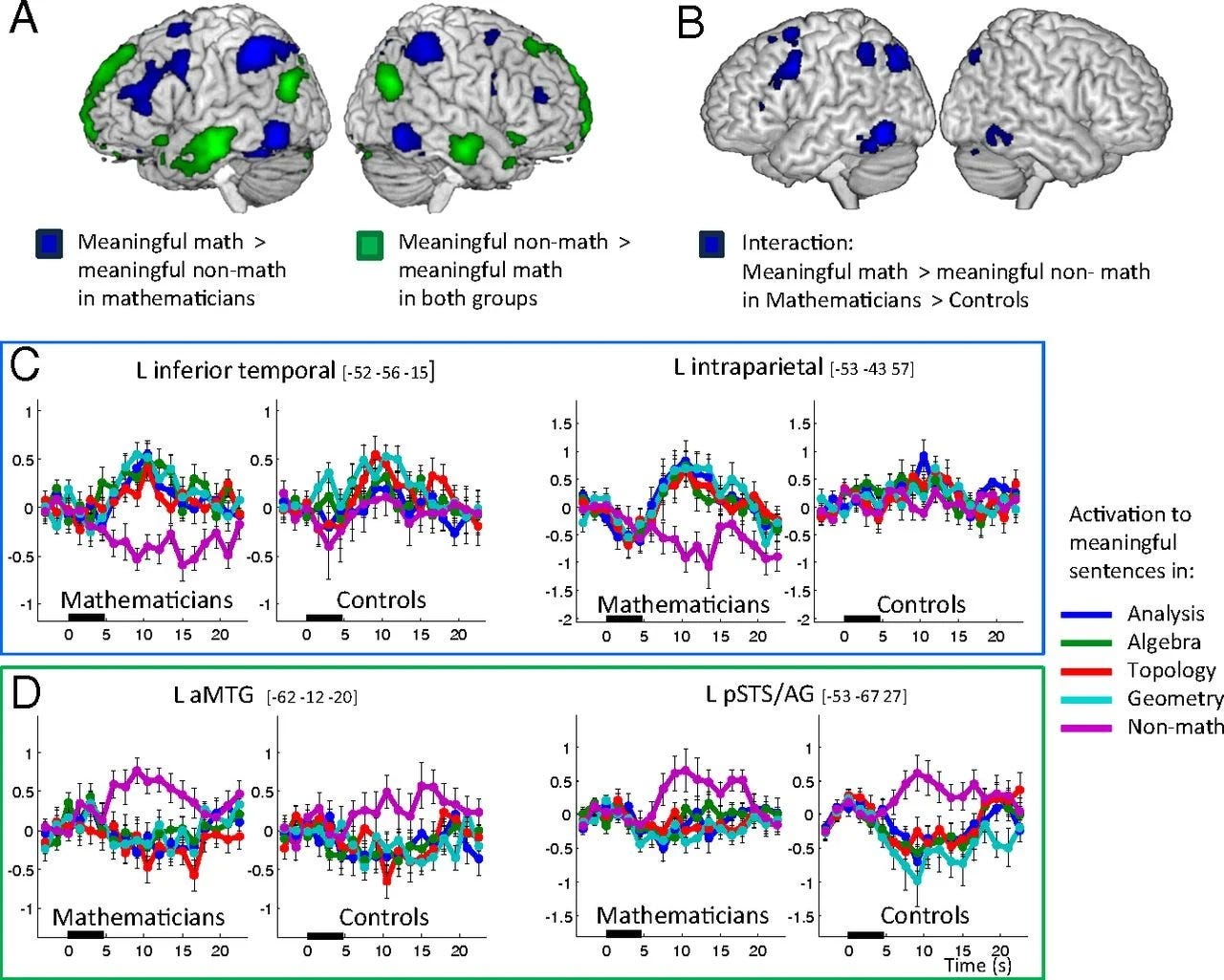

Some existing empirical evidence is directionally aligned with the conjecture. In a fascinating 2016 fMRI study, Marie Amalric and Stanislas Dehaene observed that professional mathematicians process complex mathematical statements by recruiting brain areas that aren’t typically mobilized in language processing, specifically in the inferior temporal and parietal regions. This happens regardless of whether the statements belong to their specific domain of research. By contrast, the control population of non-mathematicians with equal academic standing activate the expected language-processing regions when exposed to the same mathematical statements.

This aligns well with my subjective experience. When confronted with a mathematical statement that isn’t immediately obvious to me, I consciously switch to a special “math mode” where I try to “see” things in a certain way, to “feel” their presence and “interact” with them as if with imaginary body parts.

This peculiar way of channeling my attention developed over time. At first it was quite demanding, then it became second nature. When it involves mathematical objects that are familiar to me, it can be effortless.

The Amalric-Dehaene study only concerns reactive brain activity, when prompted with a mathematical statement. But mathematicians preemptively practice all day long, through peculiar rumination techniques that slowly enhance their intuitive comprehension.

When Einstein insists that he is only “passionately curious,” when Grothendieck declares that “the quality of the inventiveness and the imagination of a researcher comes from the quality of his attention, listening to the voice of things,” I believe that they are talking about activities of this very nature.

Strikingly, Descartes’s entire approach can be reinterpreted in those terms. This passage from his Rules for the Direction of the Mind makes it clear that the method was really about attention control:

The whole method consists entirely in the ordering and arranging of the objects on which we must concentrate our mind’s eye if we are to discover some truth.

Conjecture 3 is again compatible with the hereditarian worldview. On paper, this ability to access these special brain modes and maintain them with sufficient intensity and duration could very well be innate.

Interestingly, many people spontaneously default to this genetic interpretation when they are presented with measurable biological differences between brains.

This reveals a double standard. When hearing that brains of professional mathematicians have specific activation patterns, they feel vindicated in their hereditarian beliefs. Yet they accept non-genetic causes for the biceps of a bodybuilder or the liver of an alcoholic. Because cognitive activity takes place under a veil of invisibility, people underestimate the magnitude of the practice gap.

Conjecture 4. Most of these differences in mental habits and metacognitive approaches are acquired.An essential caveat: acquired isn’t equivalent to nurtured. Many things are acquired that are extremely hard, if not impossible, to intentionally nurture or self-develop. By acquired, I simply mean that most of these differences cannot be attributed to genetic variance and are best understood as developmental outcomes—the divergence emerges and gradually widens throughout the long and messy process that starts with the egg’s fertilization and continues into adulthood. (Which doesn’t mean that genetic variability has no influence—it is very likely to have a substantial influence, yet not predominant.)

The conjecture is intentionally vague and hard to test, and should rather be viewed as a generic pattern for building more modest, falsifiable predictions.

A concrete approach would be to create longitudinal versions of the Amalric-Dehaene study, especially ones covering the peak neuroplasticity period of early infancy. My hunch is that there are multiple neurodevelopment pathways, and each child follows a singular trajectory shaped by a unique combination of genetic, cultural, and emotional factors, and also freak events—with long-term consequences on their cognitive style.

But these early childhood studies would come with many ethical issues, as well as practical ones.

A simpler version would be to follow older students through predictably decisive stages of their progression. The French preparatory classes system is a good example. It takes “gifted” 17-18 year-olds and submits them for two years to an incredibly ambitious boot-camp-style math curriculum, a make-or-break experience that produces remarkable outcomes as well as disastrous ones (with less than 1% of the world population, France has received nearly 20% of all Fields medals ever awarded; but many students are left traumatized.)

These were transformative years for me, in the most profound sense. Something radical changed in my attention mechanisms, imagination techniques, and ability to suppress intellectual fear. The only expression that I can think of is cognitive transmogrification.

My prediction is that the progress trajectories of individual students throughout these two years would be significantly correlated with the emergence and/or reinforcement of the specific Amalric-Dehaene “math brain” activation patterns (which may or may not have been readily detectable at the beginning of the program).

Conjecture 5. Differences in mental habits and metacognitive approaches compound, over time, into measurable differences in cognitive ability. This one basically says that Einstein was right, and that this really is about developing the right kind of curiosity.

A fair objection is that Conjecture 5 is too vague. Another fair objection is that it is circular, unless one finds a reliable way of untangling the causality. Do people become smarter because they’ve discovered the secret curiosity mode, or do they discover it because they’re already smarter? (There is no reason to expect a binary answer, as cognitive development is an ongoing process with obvious feedback loops.)

While it is vague and speculative, I personally find it clarifying.

From a machine-learning perspective, the conjecture can be viewed as a natural consequence of the prior ones. Indeed, our synaptic connectome reconfigures in response to not just primary stimuli—the raw sensory signal we receive from the world—but also secondary stimuli, the stream of mental imagery that we continuously elaborate.

This is the fundamental reason why educational interventions so often fail to move the needle. While they deterministically alter the primary stimuli, their impact on the secondary stimuli is always indirect and contingent to uncontrolled factors.

This suggests bolder, reinforced versions of Conjecture 5:

Conjecture 5 bis. In humans, advanced cognitive development is primarily mediated by secondary stimuli. Genetics do define a ceiling that varies from one person to another, but very few people ever approach their ceiling and, in practice, much of the observed cognitive variance is attributable to differences in the intensity and quality of secondary stimuli.Conjecture 5 ter. Extreme cognitive talent is the exceptional outcome of unusually effective metacognitive approaches sustained over long periods of time, producing unusually intense and beneficial secondary stimuli.This is the fundamental intuition behind the entire framework. Why do we dream? Why do we constantly imagine things? Why do we experience this bizarre thing that people call a stream of consciousness? These capacities are metabolically expensive and, on the face of it, entirely reckless—we are constantly retraining our brains on our own hallucinatory slop.

Why did our ancestors evolve these singular behaviors, if not as cognitive reinforcement mechanisms? At the core, this is a machine-learning question. If we’re feeding this much synthetic data into our cortex, then there must be a good reason for that.

Conjecture 5 ter might be overambitious, but it provides a non-magical explanatory framework for extreme talent, consistent on many levels:

The brain activity that produces these secondary stimuli is a physiological reality with concrete, measurable manifestations.

From a theoretical machine-learning perspective, secondary stimuli are expected to have a massive impact on cognitive fitness.

According to Conjecture 3, there should exist massive measurable differences in how these secondary stimuli streams are produced from one individual to another—so cognitive inequality would at last have a physiological explanation based on something where people would exhibit massive physical variability.

As secondary stimuli aren’t part of the shared experience, and their effects compound over decades, it would also explain why cognitive inequality has this magical feel of “coming from nowhere” (hence the common hereditarian misinterpretation.)

It would align with the accounts of historical “geniuses” who insisted their abilities stemmed from practice and attention (Einstein, Descartes, Grothendieck)—and it would explain why they struggled so much to find the right words.

The 20% full glass

Returning to solid ground, the natural question is this: assuming that the framework is directionally correct, what are the practical consequences?

If you dislike hereditarianism because it doesn’t leave enough room for human agency, then my answer might not leave you entirely happy.

The human brain is a fabulously complex, non-linear device with multiple layers of feedback loops, which makes its behavior inherently hard to control.

There is ample evidence that key aspects of cognitive inequality have already crystallized by the time children acquire the language capability to make sense of metacognitive guidance. Whether it’s the genetic lottery, the socioeconomic lottery, or the idiosyncratic neurodevelopment lottery, the conclusion is basically the same: you cannot train your kid to become the next Einstein.

There is, however, a crucial nuance. Mental habits and metacognitive approaches cannot be directly transferred from one brain to another, but it is possible to discuss them—or at least try to—and everyone has a meaningful margin for improvement.

This is the 20% full glass and, however depressing it may look from afar, it is worth your time and effort.

I am familiar with this bizarre, seemingly contradictory feeling. Like many math students, I was shocked by the immensity and apparent immutability of the talent gap. My standing in the math cognition hierarchy seemed determined once for all in a relatively boring place, far above “normal people” and far below “the geniuses”. And, in a sense, this is where I have always remained—far above “normal people” and far below “the geniuses”.

But the talent gap is so wide that this isn’t a well-defined spot. With a three-decades hindsight, it is also clear that the math cognition hierarchy of my peer group wasn’t truly static. In fact, there have been some impressive upward and downward trajectories.

For me, the hardest part wasn’t to identify the right mental habits—I had a clear enough idea from my early 20s—but to cobble together the courage and resilience to practice them with more discipline.

No theory of cognitive inequality would be complete without a discussion of fear. Why did we evolve cognitive inhibition, this bizarre response to intellectual difficulty, this visceral panic, this brain fog that prevents us—among other things—from even engaging with mathematical abstractions?

Interestingly, Conjecture 5 bis contains a tentative explanation. Learning from our own imaginary stimuli is a risky business that isn’t supposed to work unless the right conditions are met. It can improve our cognitive fitness, otherwise we would have gone extinct. But we know of many circumstances where it has the opposite effect (superstitions, cults, paranoid delusions…)

This final conjecture might be overambitious and, in any case, it is hard to validate or falsify:

Conjecture 6. Cognitive inhibition is an adaptive protection against learning from unreliable mental imagery, which must be overcome to unlock creative thinking and mastery. It is partially regulated by social feedback, resulting in a self-reinforcing cognitive stratification that crystallizes with age.It mirrors a subjective experience shared by many mathematicians, who insist on the prominent role of self-confidence. Here is a striking passage from Bill Thurston’s celebrated essay On Proof and Progress in Mathematics:

It regularly happens that someone who was in the middle of a pack proves a theorem that receives wide recognition as being significant. Their status in the community—their pecking order—rises immediately and dramatically. When this happens, they usually become much more productive as a center of ideas and a source of theorems. Why? First, there is a large increase in self-esteem, and an accompanying increase in productivity. Second, when their status increases, people are more in the center of the network of ideas—others take them more seriously. Finally and perhaps most importantly, a mathematical breakthrough usually represents a new way of thinking, and effective ways of thinking can usually be applied in more than one situation.

This is a perfect illustration of the 20% full glass. We do perceive fairly rigid cognitive hierarchies and, to a certain extent, this perception is correct. Yet these hierarchies are far less rigid when we look at individual trajectories over long periods of time, which is the right perspective for thinking about our future. Progress involves reinforcing self-confidence, finding the right sparring partners and ecosystems, and developing new ways of thinking.

If intelligence is primarily embodied in our connectomes (Conjecture 2), then we should think about it in the same way we think about wealth, as the continuing outcome of a non-deterministic capitalization process.

The 80% empty glass is that life is unfair and we cannot replay the past. There are no miracle people, but there are miracle trajectories.

The 20% full glass is that the one thing that is truly ours—our attention, the focus of our curiosity, how we navigate our stream of consciousness—may matter more than we ever dreamed.

This is so intriguing. I'm wondering about this passage: 'This is the fundamental reason why educational interventions so often fail to move the needle. While they deterministically alter the primary stimuli, their impact on the secondary stimuli is always indirect and contingent to uncontrolled factors.' Could you give an example of a 'secondary stimulus' to clarify it a bit? And of uncontrolled factors?

Hi David, lovely post. It resonates deeply with something I've been working through - not just understanding how metacognitive habits differ, but actually changing them in practice.

Some months ago, I started thinking about the brain as fundamentally conservative, settling into stable attractor states. The brain can't run on nouns - it needs trigger → action → feedback. Some stimuli comes in, the brain responds with a practiced move, and keeps going until it gets relief (prediction error drops). Most of our daily actions - maybe 95%+ - are repetitions of moves we've done before given the same triggers. You can see this vividly in something like football. Watch players dribbling and their gaits are nearly identical match to match. The brain finds movements that work and defaults to them because it's metabolically cheap.

The same thing happens with thinking. When students hit confusion, they cycle through remarkably predictable policies: re-read, ask "why don't I get this?", check the answer key, or skip it. The feedback loop closes - uncertainty gets temporarily resolved - and the brain marks this as successful even though nothing was actually learned.

Looking back at my own learning, I realized every time I got unstuck after prolonged struggle, it was after some pivot or action - trying a diagram, computing a case, explaining to myself. Never did wheel-spinning in the same mode resolve confusion.

What I also noticed was that often it took me extended periods of time to get unstuck - not because the problem was that hard, but because that's how long it took for desperation to build up enough to lower my threshold for seemingly absurd action. Action that then, to my surprise, actually resolved the confusion. But I'd never systematized this or looked at what preceded breakthroughs.

What I settled on was: detect confusion early and immediately force a representational shift. Switch from algebra to geometry, symbolic to numerical, abstract to physical - whatever gets you out of the current stuck state.

This maps directly onto your point about secondary stimuli. The difference between someone stuck and someone learning isn't the problem itself but what they do internally when stuck. Re-reading the same passage generates almost no new neural activity. Switching representational modes - visualizing geometrically, computing specific examples, explaining out loud - activates completely different pathways.

But here's the implementation problem: at peak uncertainty, when you're most confused, your capacity for novel action is lowest. This is exactly when the brain defaults to familiar ineffective responses. Knowing you should shift representations changes nothing.

What actually worked was externalizing the choice. I made cards with specific moves: "Compute Something," "Extreme Cases," "Remove One Part," "Reverse/Rotate/Swap," "Sit With Confusion," "Make Prediction." When stuck, I draw a card. This removes the hardest part - committing to action under uncertainty. Any shift away from the stuck state generates information.

The second thing: permission to execute wrong. After some initial tries, I came to find there's usually this hesitation where you're evaluating "how exactly should I do this?" That evaluation overhead often kills the attempt. Slows you down. So instead: execute wrong on purpose! Don't know which numbers to compute? Use obviously wrong ones. Try the extreme case even if it seems absurd. I found wrong execution generates information fast - you learn why it's wrong in seconds, which reveals constraints and hidden structure.

I realized that confusion as a state is actually rather similar across different domains. The brain being what it is - a trigger-action-feedback system - if I could install a different state-action mapping at this inflection point, it should have outsized effects. If the new policy reduces prediction error better than the old one, it should outcompete it naturally over repetitions.

And it did. After some weeks of forced practice with the cards: detection latency dropped from 90 seconds to maybe 20-30, execution became nearly immediate, and subjectively I started feeling 'restless' when stuck and not shifting. The new policy's prediction-error-reduction is so much better that staying in one representation now feels 'wrong'. That restlessness is the experiential signature of attractor replacement.

What strikes me is the magnitude of improvement relative to effort. Problems I previously thought required checking textbooks or were just beyond me now resolve through sustained exploration. It takes longer than looking up answers, but I build actual understanding and the capability to do it again.

The old policy feels like doomscrolling - minimal cognitive load, no new information, just anxiety relief. The new policy feels like exercise - more effortful initially, but generating new neural activation with each attempt.

Your secondary stimuli insight is particularly apt here. Each representational shift isn't just "thinking harder" - it's generating different internal experience. Algebraic manipulation, geometric visualization, numerical calculation activate distinct neural substrates. High-frequency switching means high-diversity neural exploration, which should drive connectome reorganization much faster than passive re-reading.

Before this I was cognitively sedentary when stuck - burning mental energy on anxiety while generating minimal neural activity. Now there's constant motion: try this angle, doesn't work, try that, learn something, try another. The volume of distinct cognitive states explored per unit time has increased dramatically.

But I think the compounding goes deeper than just executing pivots more reliably. The brain being a pattern-matching machine, over time it comes to map certain kinds of cues - internal or external - with certain moves. It realizes some moves work better to resolve prediction error than others as it gathers experience. This is essentially what intuition is.

The increased information density per unit time, from this active learning strategy, means the brain gets vastly more data to identify underlying patterns. Each night when you sleep, the brain compresses this enormous amount of information, replays it, consolidates it. Over months and years, this might explain how people who naturally default to this stance appear to have better "smell" for what to do and when. It compounds exponentially.

It's really akin to what you described as going into "math mode" - and what you said elsewhere: "This bizarre, almost childish attitude is extremely hard to communicate to outsiders." That's exactly it. It's like a kid picking up a toy and figuring out all the funny ways they can play with it, learning about its properties in the process. The little moves are cheap, easy. If they don't work, it doesn't mean much - you just do something else.

I don't think any of this is particularly revolutionary from a pedagogy or neuroscience standpoint - I suspect it's implicit to how a lot of mathematicians and physicists actually work. But it was revolutionary to me personally, this shift in cognitive stance.

If intelligence lives in the connectome and connectomes reorganize in response to activity patterns, this high-frequency representational shifting should accelerate development. Not immediately, but compounded over months and years the divergence could be substantial.

I think what made this work wasn't just understanding the principle (intellectually) but the operationalization. The cards externalize the decision at exactly the moment when your brain is least capable of making it. Wrong execution removes the evaluative layer that causes hesitation. Together they bypass the exact bottlenecks that prevent people from using techniques they intellectually know about.

This seems to instantiate your conjectures directly. The cards operationalize a specific trainable habit at the exact inflection point that determines learning trajectories. Within weeks of deliberate practice, a completely different response pattern installed itself.

Motion precedes clarity. That's the stance you start to embody.

Being an optimist, I think you might be understating the potential magnitude. If the constraint on cognitive development is primarily metacognitive habits rather than genetic ceiling, and if simple protocols can shift those habits within weeks, the accessible improvement might be larger than the "20% full glass" suggests.

The protocol costs essentially nothing - some index cards and permission to execute badly - but it forces precisely the kind of "peculiar rumination techniques" you describe elite mathematicians practicing. It's a way to operationalize what you call quality of attention, but as concrete actions anyone can systematically train.

Most importantly: it's trainable in the sense of actually installable, not just intellectually understandable. You need a detectable trigger, an externalized action protocol, permission to execute imperfectly, and volume of practice. The policy that better reduces prediction error wins naturally. No willpower required once the initial pattern starts to dominate.

Thanks for articulating this framework so clearly. It's nice to see my experience map onto your educated guesses about secondary stimuli, metacognitive habits, and compounding neural differences.