Thinking fast, slow, and super slow

How mathematicians train their intuition

A ball and a bat cost a total of $1.10. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

I borrowed this problem from Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. I encourage you to try it with your friends. Most people will answer that the ball costs 10¢, but that’s not the right answer. If the ball cost 10¢, then the bat costs $1.10—since it costs $1 more than the ball—and the ball and the bat together cost $1.20.

If you tell them why their answer is wrong, your friends will get it easily enough. But they won’t necessarily know the right answer. They’ll even find tons of excuses to not look for it: it’s hard to do the calculations, they’d have to write down the equations but they don’t have a pen, they can’t be bothered, whatever…

The correct answer is 5¢.

The ball and bat problem is a perfect illustration of the theory of cognitive biases, which Kahneman developed with Amos Tversky. According to this theory, we have two distinct cognitive systems, System 1 and System 2.

System 1 allows you to give immediate and instinctive responses, without even trying. When someone asks you how much is 2 + 2, what year you were born, or which weighs more between an elephant or a mouse, you don’t even have to think. But it’s also System 1 that makes you answer, incorrectly, that the ball costs 10¢.

System 2 is what you have to use when you’re asked to calculate 47 x 83, or how many days have passed since your birth. You know how to get the answer, but you’d have to think. You probably need pencil and paper. One thing is certain: you don’t really want to do it. Even if System 2 is more reliable and rigorous, you only use it when you have no other choice, because thinking hard, doing calculations, and logical reasoning are all tiresome.

The theory can be summed up as follows:

Each time our System 1 gives us an answer, we’re tempted to use it without calling on System 2, not even to verify that the answer is correct. Because System 2 uses a lot of mental energy and resources, we primarily rely on our instinct. Biologically, we’ve developed a preference for intellectual laziness.

In certain situations, our System 1 is systematically wrong. We all make the same mistakes, all the time, as if the wiring schematic in our brain was defective. These are the “cognitive biases” that the theory aims to study. We all want to say that the ball costs 10¢.

Kahneman’s book became a best-seller in part because it went beyond the simple theoretical observation and proposed a concrete method to avoid falling into the trap.

He has a simple recommendation: learn the list of cognitive biases presented in his book by heart, and each time you recognize one of the typical situations, fight your inclination and use your System 2 while trying to ignore your System 1.

I think there is a better way of doing it, which I’ll explain.

“That’s cheating!”

The first time I heard the story of the ball and the bat, it was from a friend who was studying cognitive science at Princeton. She had just read Kahneman’s book and wanted to do the test with me.

Like most people, I gave an instinctive response. I listened to my System 1 without knowing it was called System 1. Without thinking, without doing any calculations, I gave the first answer that popped into my head: “5¢.”

I felt that my answer annoyed my friend but I didn’t immediately know why. She took the time to explain what was up. I was supposed to answer “10¢,” or at least take a few seconds before answering “5¢.” At any rate, there was no way I was supposed to answer “5¢” immediately, without taking the time to think about it. That was simply not allowed. A guy had even won the Nobel Prize for showing it was impossible.

Quickly enough, right before changing the topic of conversation, my friend did however come up with an explanation—a simple, pragmatic, and not entirely false one:

That’s cheating! You’re a mathematician!

When I had my friends and colleagues take the test, I was sincerely surprised to find that so many of them answered 10¢, and even more surprised at their difficulty in finding the right answer after admitting that their initial response was wrong. The most incredible thing was that everyone spoke to me about “doing the calculations,” as if there were any need for that, as if it weren’t visually evident that the right answer was 5¢.

A or B

This ball and bat story began to really intrigue me. I tried to understand what was stopping my friends from seeing the right answer when it was so obvious. I did my own little investigation and I believe I have found an explanation.

After asking my friends about the price of the ball, I followed up with this question:

Imagine that you have to make an important decision in your life. You have the choice between option A and option B. Your intuition tells you to choose A, but your reason tells you to choose B. What do you do?

I presented this question to more than a dozen of my non-mathematician friends, and almost all of them answered, without hesitation, that they’d follow their intuition and choose A. Only one person chose B. Another hesitated for a long time, without ever giving a clear response.

Nothing guarantees that you’d get such a high percentage of people choosing A if you tried this experiment on your own. My protocol suffers from what is called selection bias, in that my friends aren’t necessarily representative of the general population, and it may very well be that people who listen to their intuition have greater chances of becoming my friends.

The exact proportion of A and B didn’t really interest me. What I wanted to know was whether someone would come up with the same response I would have given myself. No one did.

My hypothesis is that my unusual response to the question is the key that allowed me to become good at math and, along the way, to reeducate many of my cognitive biases.

This isn’t a reasonable assumption

Kahneman says that thousands of American students took the ball and bat test, and that “the results are shocking.” At the lower-tier universities, the error rate was over 80%. Even students at Harvard, MIT, and Princeton gave the wrong answer more than 50% of the time.

Kahneman’s book is fascinating, but I’m confused whenever I see him opposing “the right answer” and “the intuitive answer,” as if there were only one intuitive response possible, and it was necessarily false. For example, he writes:

It is safe to assume that the intuitive answer also came to the mind of those who ended up with the correct number—they somehow managed to resist the intuition.

In other words, Kahneman finds it safe to assume that I shouldn’t exist. My opinion, understandably, is that this isn’t a reasonable assumption.

But beyond the relatively minor question of my own existence, this anecdote reveals a major disconnect between Kahneman’s theory and what all mathematicians know deep in their bones. It’s up to you to decide who’s in the best position to give you advice on mental calculations.

Kahneman finds it shocking that 50% of the students at Harvard, MIT, and Princeton blindly relied on a manifestly false intuition, and I am as shocked as he is.

But I am equally shocked by something that Kahneman apparently finds completely normal: how is it that 50% of the students at Harvard, MIT, and Princeton managed to get accepted despite having such faulty intuitions?

Having studied and taught at highly competitive universities, I know that students who can directly “see” the correct answer in their head have an enormous competitive advantage. I don’t understand how the others can even compete. I imagine that they compensate by intensive cramming, something I’m completely incapable of and the very thought of which gives me a headache.

Kahneman’s advice consists of identifying the situations where we should “resist” our intuition and submit ourselves to System 2. It’s strange advice coming from someone who’s spent his life documenting our aversion to effort, our preference for instinctive and immediate responses, our immoderate love for System 1—and our hatred of System 2.

This idea that we should resist our bad instincts and entirely submit to a robotic mode of thought was once the prevalent paradigm in education. Kahneman is well enough placed to know why it can’t work.

Another point bothers me. It’s true that we should be wary of our System 1. But what are we to make of our System 2? Personally, I stopped trusting mine after ninth grade, when I found out I wasn’t able to string together three lines of calculations without making a mistake.

But the most troubling aspect is that Kahneman reasons as if our intuition were hardwired, with no possibility for us to reconfigure or reprogram it. Had he lived in the ancient Roman era, he would almost certainly have said that it was impossible to represent mentally the result of the operation 1,000,000,000 - 1, because the number greatly exceeded the capacities of human intuition.

System 3

When I need to make an important decision in my life, if my intuition tells me to choose option A and my reason tells me to choose option B, I tell myself there’s something going on and I’m not ready to make the decision.

That’s the moment to resort to what I call System 3.

System 3 is an assortment of introspection and meditation techniques aimed at establishing a dialogue between intuition and rationality. You use it each time you try to recall your dreams, to put words to the fleeting impression that left a strange taste in your mouth, to sort out your most confused and contradictory ideas.

When I was eighteen and I discovered that the stupid images in my head had a tendency to correct themselves once I made the effort to describe and name them, when I got into the habit of lending an ear to the dissonance between my intuition and logic, I put System 3 at the center of my strategy for learning math. The results exceeded my wildest expectations.

We all know System 3 and we all use it, at least from time to time. My mathematical journey taught me that a voluntary and radical use of System 3 is not only possible, it augments our intuitive capacities well beyond the supposed limits of human cognition.

Through the years, the systematic search for a better alignment between my intuition and logic has become my way of understanding the world, others, and even myself.

In practical terms, here’s what that means. When my intuition tells me A and rationality tells me B, I put myself in the position of a referee. I force myself to translate my intuition into words, to tell it like a simple and intelligible story. Vice versa, I try to picture what logical reasoning is actually expressing, to experience it in my body, to hear what it’s trying to say. I ask myself if I really believe it. I fumble about. It takes time but it’s not a real effort. It’s more like a meditation on running water, something going on in the background that might stop and start, then all of a sudden become clear days, months, or even years later.

The goal is to understand where things are going wrong. Are my intuition and logic even speaking the same language? Are they even talking about the same things?

My intuition is never perfect. It’s often relevant, but sometimes it’s just rubbish. The good news is that it’s generally fixable. As for logic, that’s never wrong. At least officially. Except that it doesn’t necessarily say what I think it’s saying.

In the end, it’s almost always my intuition that wins. When I force it to listen to what logic is saying, it takes that into account and adjusts its position. Logic is something inert, like a pebble. My intuition is organic, it is living and growing.

It’s obviously stupid to call this approach System 3. It should simply be called thinking or reflecting. But the meaning of these words has been hijacked by a tradition that wants to make us believe that we should think contrary to our intuition. We’re told that our intuition is the mortal enemy of reason, that any dialogue between the two is impossible, and thinking means you have to submit blindly to System 2.

I’m personally incapable of thinking against my intuition and I have serious doubts as to the sincerity of people who claim they can.

Your intuition really is your most powerful intellectual resource. However, at the risk of spoiling your dreams, I must be honest with you—your intuition isn’t a magical elixir, or your lucky star, or the hand of God on your shoulder. It’s much more trivial than that. It’s the tangible manifestation of something that is invisible yet perfectly concrete and material: the entanglement of synaptic connections between your neurons that your brain continuously constructs and reorganizes, as it has done since you were in the womb. Your brain contains roughly as many neurons as there are stars in the Milky Way. Each of these neurons is, on average, tied to thousands of other neurons. This fabric of hundreds of trillions of interconnections is the network of your mental associations. Its structure is your way of giving meaning to the raw information continually flooding into your brain. This is, literally, your vision of the world. All that you have seen, heard, felt, imagined, or desired, all of your experience, all that you know, all that you remember, is encoded in this web. When your intuition speaks, that’s where it’s speaking from.

Your intuition will always be more powerful and better informed than the most sophisticated of language-based reasonings. For all that, it’s not infallible. If your intuition tells you the ball costs 10¢, it’s plainly wrong.

My intuition isn’t any less fallible than yours. It’s always getting things wrong. I have, however, learned never to be ashamed of it. I don’t disdain my mistakes, I don’t push them aside, because I don’t think that they betray my intellectual inferiority or some cognitive biases hardwired in my brain. On the contrary. Nothing’s more exciting than a big glaring error: it’s always a sign that I’m not looking at things in the right way, and that it’s possible to see them more clearly. When I’m able to put my finger on an error in my intuition, I know it’s good news, because it means that my mental representations are already in the process of reconfiguring themselves.

My intuition has the mental age of a two-year-old—it has no inhibitions and always wants to learn. If you stop mistreating your own, you’ll see that it’s exactly like mine, only asking to be allowed to grow.

The price of a ball

Because I have terrible handwriting, and because I’m easily distracted, I have a tendency to make mistakes in calculations.

I discovered in ninth grade that the only way to get around that was to verify after every three lines that what I was writing still made sense and that I really believed it. In other words, I learned how to use my System 1 to supervise the work of my System 2. From this time on, I was incapable of manipulating mathematical objects that I had no intuition for.

At what moment did I stop primarily visualizing numbers through their written form? I don’t recall. But it undoubtedly goes back to the same period. Decimal writing of numbers is useful for written calculations but it is certainly less practical when you want to form an intuitive idea about the validity of those calculations. This is where System 1 has an edge: it isn’t bound by the constraints of language and writing.

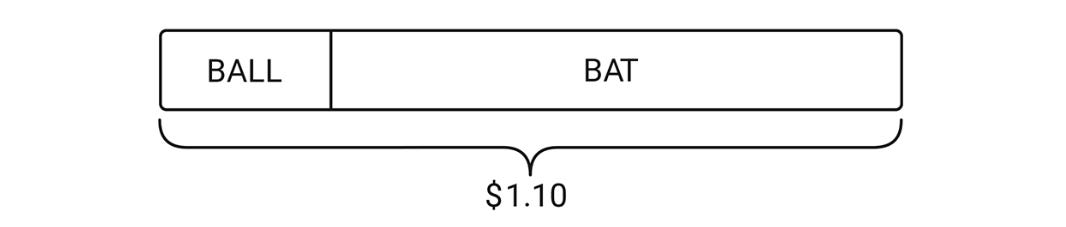

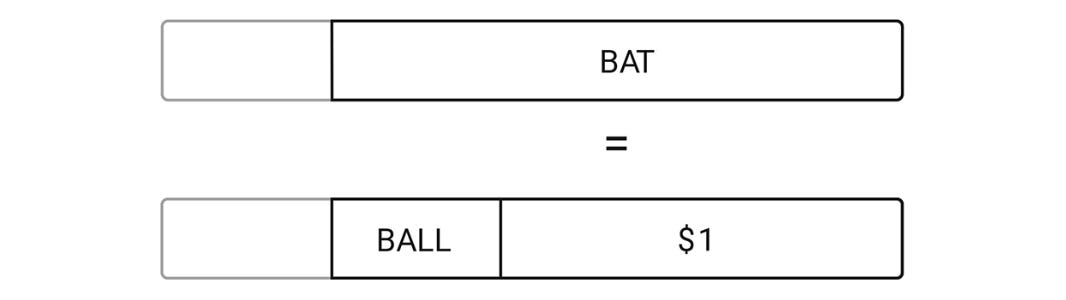

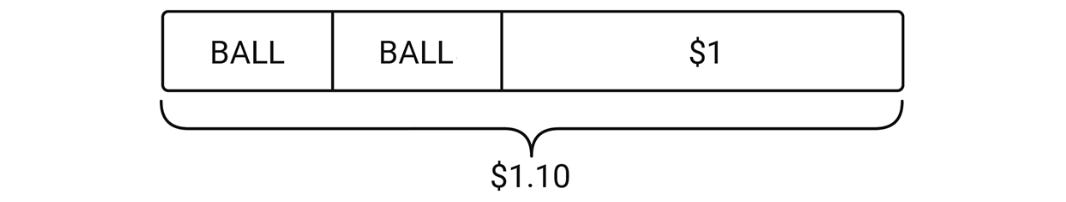

Depending on the context, I have many different ways of visualizing numbers. I have, for example, a tendency to visualize price in terms of length. When my friend told me that the ball and bat together cost $1.10, I immediately translated her words into a mental image that looked something like this:

When she told me that the bat cost $1 more than the ball, here’s how I saw it:

Then the two images came together in my head and morphed into something like this:

If this is how you visualize the problem, it doesn’t take a genius to figure that a ball costs 5¢.

A mental image is neither good nor bad in and of itself. Its value lies in what it allows you to understand. There are countless ways to visualize the problem and I don’t pretend that mine is better. My numeric intuition isn’t all that remarkable. I wouldn’t be able to do the calculation if the ball and bat together cost $2,734.18 and the bat cost $967.37 more than the ball.

I have these pictures in my head because, in my life, I have made a lot of calculation errors. Instead of concluding that I was terrible at math, I simply looked for simpler ways to see things, to grasp what I was writing.

In time, with this approach, I constructed a great variety of mental images that help me today to better understand the world—including the particular one that enabled me to find the price of the ball.

If you want to learn to find it obvious that the ball costs 5¢, I recommend proceeding like a mathematician would when faced with a new and incomprehensible idea. Rather than learning my pictures by heart, train yourself to construct pictures that work for you. The most important messages, the ones you should always bear in mind, are these:

You can reprogram your intuition.

Any misalignment between your intuition and reason is an opportunity to create within yourself a new way of seeing things.

Don’t expect it all to come at once, in real time. Developing mental images means reorganizing the connections between your neurons. This process is organic and has its own pace.

Don’t force it. Simply start from what you already understand, what you can already see, what you find easy, and just play with it. Try to intuitively interpret the calculations you would have written down. If it helps, scribble on a piece of paper.

With time and practice, this activity will strengthen your intuitive capacities. It may not seem like you’re making progress, until the day the right answer suddenly seems obvious.

You’ll need a number of training sessions. Exactly how many, I don’t know. It’s not worth tiring yourself out—better to split it up into short five-minute sessions, and think about it in the shower or while on a walk. Some people told me they could visualize the ball-and-bat problem in under a week, but your mileage may vary.

Above all, take your time. It’s good to think about it only once a week or once a month. Most important, keep at it and don’t let it drop. It will come eventually.

Solving a problem is only ever a pretext. The important thing is that you have the power to reeducate your intuition, to gain confidence in your body and thoughts.

Nothing about this should surprise you. Solving the problem of the ball and the bat is like standing up on a surfboard. Kahneman says that the first time you stand up on a surfboard, you’ll fall in the water, and concludes that humans are born with a defective sense of balance and that getting up on a surfboard can never become intuitive. His advice is to get out of the water and learn the laws of physics by heart. My advice is to get back up on the board.

Thinking fast, slow, and super slow

Our culture conveys false beliefs about how our brain functions, and that these false beliefs keep people away from the simple actions that would allow them to become better at math.

When you say to people that certain truths are by nature counterintuitive, you tell them that they can never really understand. It’s a way of discouraging them. Nothing is counterintuitive by nature—something is only ever counterintuitive temporarily, until you’ve found means to make it intuitive.

Understanding something is making it intuitive for yourself. Explaining something to others is proposing simple ways of making it intuitive.

None of this takes away from the value of Kahneman’s work. The cognitive biases that he documents are striking human realities of great social importance. We all have biases, even if they aren’t hardcoded and vary from one person to another, and certain biases happen to be more widespread and problematic than others.

His distinction between System 1 and System 2 has the merit of being simple. In a sense, it picks up the classic opposition between left brain and right brain, but in a modern version, without the anatomical nonsense. It’s just a basic model, but it’s appealing, and helps us become aware of our different ways of mobilizing our mental resources.

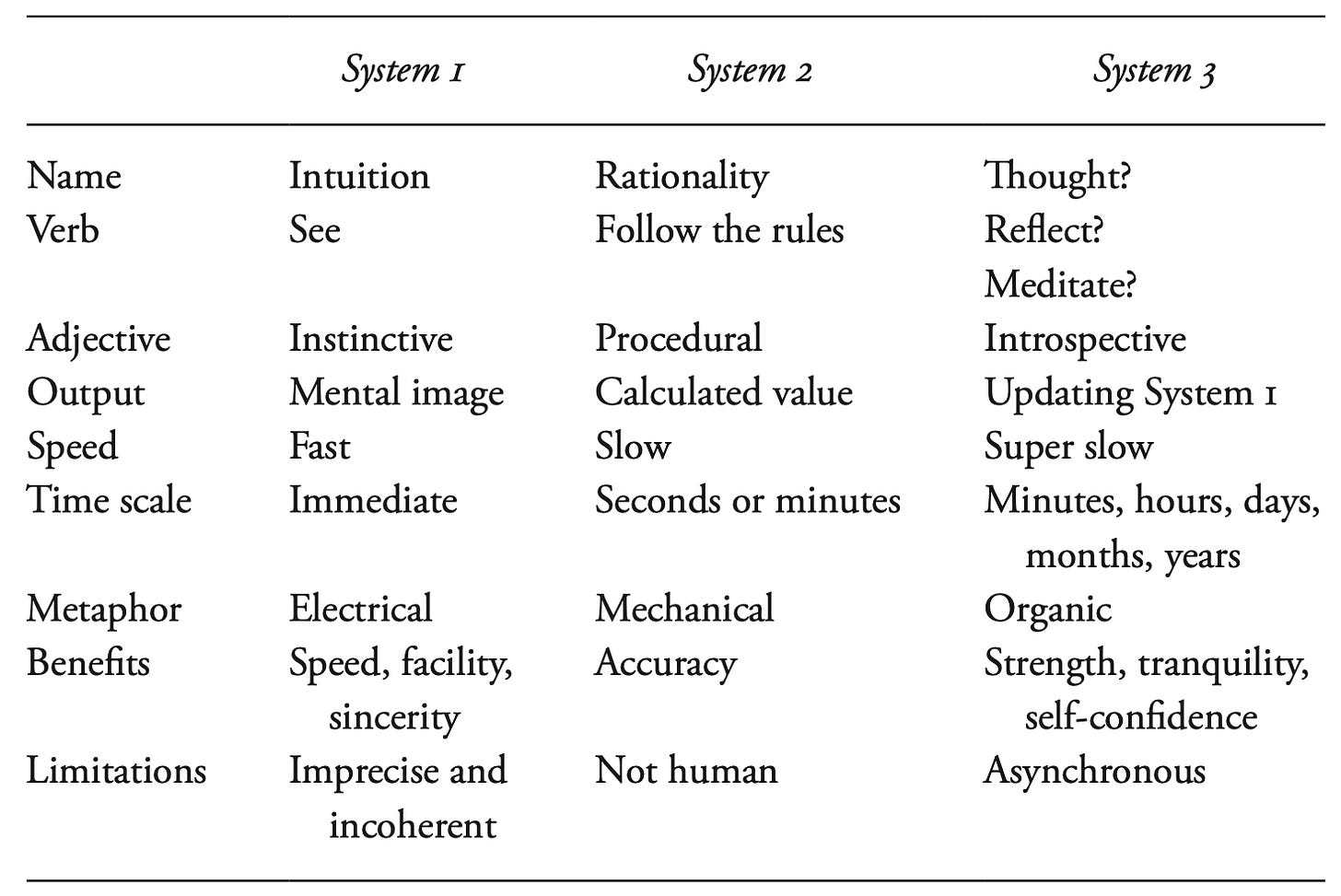

Here is a quick summary of the characteristic principles of System 3, the big oversight in Kahneman’s theory. It is a good model for the real nature of mathematical work.

System 1 is our intuitive capacity. We all like to describe it using electrical metaphors: with our intuition, we say that we think with the speed of lightning. It’s not entirely false. Our brain isn’t properly speaking an electrical circuit, but the signal that’s transmitted along the neurons is electrical in nature.

System 2 is our capacity for rigorous reasoning. We imagine it in mechanical terms, with gears or something of the sort. That doesn’t correspond to any biological reality. What we are biologically capable of is to pretend we’re robots and mechanically apply a preset series of instructions. With the right set of instructions, we can make logical conclusions and valid calculations. But it’s so disagreeable and against our nature that we usually give up after a few seconds, or at most a few minutes. In the end we’re rather sorry robots: we make too many mistakes and we can’t go the distance.

System 3 is so entirely ignored by our culture that I can’t find the right word to characterize it. As I said above, I would like to say that System 3 simply corresponds to our capacity for thinking. But the verb to think doesn’t mean much since it’s been used as an injunction to submit to System 2.

The activity of System 3 is a special kind of meditation, but this word is also much too vague. Not all meditation is an activity of System 3. System 3 specifically aims at establishing a dialogue between Systems 1 and 2, in order to understand their misalignments and resolve them. Rather than a free meditation, it’s one constrained by the principle of noncontradiction. Its ultimate goal is to revise and update System 1 while taking into account the results of System 2.

It is also necessary to distinguish System 3 from the capacity of our System 1 to revise itself without any deliberate action on our part. Our mental plasticity results from the constant reconfiguration of our synaptic network: our mental circuits evolve in response to our experiences. You can imagine neurons as minuscule plants that grow and sink their roots deeper and deeper.

Every time we practice a given activity we habituate our System 1 to the specifics of that activity. When we try to stand up on a surfboard, we habituate our System 1 to the hard realities of Newtonian physics and construct our surfing instincts. With System 3, we habituate our System 1 to the hard realities of logical consistency and construct our instincts for truth.

The great misunderstanding of math teaching stems from the fact that all the tangible manifestations of mathematics—its confusing language, its incomprehensible notation, its bizarre and rigid reasoning—seem to tie it to System 2.

Most people take that at face value. They become discouraged in a few minutes, or throw themselves into a masochistic effort that has zero chance of succeeding.

But a few people choose to rely on their System 3. They’re not aware that they’re doing anything special. Math just feels easy to them. It doesn’t even feel like work. They’re just seeing pictures in their heads, and spending a couple of minutes a day looking at these pictures and asking themselves naïve questions.

To them, it all looks completely normal. It certainly doesn’t feel like they have a gift.

This post is adapted from Chapter 11 of Mathematica: A Secret World of Intuition and Curiosity.

Something is happening with this famous example that makes people fail so reliably. Essentially, it is using a “magician’s force.”

If the ball cost problem was presented mathematically like:

x + (x + 1.00) = 1.10

I doubt that the failure rate of University students would still be 50%. Would it be 5% or 0.5% or lower? Probably.

The wording of the problem is intended to engage a verbal attempt at solving it. Remember all the parsing needed to pull meaning from the scenario.

“A bat and ball cost $1.10”

(Two objects are presented in a specific order, and equated with a number also separated in order by two pieces by the decimal. The first object is bat and the first number segment is a dollar; the second object is ball and matches ten cents. Even if the problem is read aloud, “dollar ten” is still two ordered items. This results in:

{bat, dollar}, {ball, ten cents}

Next is the direct sentence further suggesting the cost of the bat is a dollar.

“The bat cost $1...”

Of course, left alone it would be a direct lie, but it continues “more than the ball.”

Since a dollar is more than 10 cents the bat would certainly cost more than the ball. A true statement. The lack of a comma means we are supposed to parse “more” in the sense of an inequality and some people recognize that and restructure the scenario mathematically. But most people will not jump off the initial word base association that was “forced” onto them.

“A Pickle and an Onion when purchased together cost 90 cents. The Onion costs twice as much as the Pickle. How much does each cost?”

How many of your friends would fail simple math problems when presented without the magician’s force?

I and many of my peers, when struggling with an academic topic, would receive the confusing injunction to apply ourselves. I'm not sure anyone who said it could articulate what applying one's self is. They might have had something shaped like system three in mind, however vaguely. Applying one's self likely also involves something else. But system three is a start.