Writing is hard — and it should be

The excruciating art of clarifying your mind

My dear Serre,

Thanks for the various papers you’ve so generously sent me, as well as for your letter. Nothing new here. I’ve finished my ridiculous piece on homological algebra (but it’s the only way I have of understanding, through sheer persistence, how things work)…

As Kevin Frey and I sat together to resolve outstanding issues in the draft of the English language edition of Mathematica, we spent twenty minutes debating this tiny passage from a 1956 letter from Alexander Grothendieck to Jean-Pierre Serre.1

We ended up agreeing on “ridiculous piece”, although we were perfectly aware that it failed to capture the full expressivity of “emmerdante rédaction”, the original phrase used by Grothendieck. Here’s how Claude puts it:

The phrase “emmerdante rédaction” is particularly colloquial - using a somewhat vulgar term to describe the writing as annoying or tedious, which gives insight into the informal, friendly relationship between the correspondents.

The dismissive language is stunning. Here was Grothendieck, arguably the most influential mathematician of the past century, disparaging his own Tôhoku paper, a groundbreaking work that was about to revolutionize homological algebra.

I used this quote as the opening to Chapter 7, which discusses the specificities of mathematical writing through the lens of Grothendieck’s philosophy of discovery. To Grothendieck, the essence and value of mathematics cannot be captured in writing. It doesn’t lie in formal logic or cryptic formulas (“it’s not in this form that you find the soul of understanding mathematical things”), but in the inner experience of making sense of them:

What drives and dominates my work, its soul and reason for being, are the mental images formed during the course of the work to apprehend the reality of mathematical things.

Yet, in an apparent paradox, Grothendieck was an excruciatingly careful writer, obsessed with details and exhaustivity. He spent the last decades of his life in complete isolation, producing 70,000 pages of notes on everything — his mathematical ideas, his dreams, the entire universe... He even wrote a 10-page treatise on kimchi:

The paradox is resolved once you realize that Grothendieck viewed writing, and specifically writing within the constraints of mathematical formalism and logical consistency, as an apparatus for “gathering intangible mists from out an apparent void” and solidifying them into stable mental images.

Writing isn’t optional — it is central to the process. In Grothendieck’s own words:

The role of writing is not to record the results of research, but is the process itself of research.

or, circling back to his 1956 letter:

it’s the only way I have of understanding, through sheer persistence, how things work.

Short form vs long form vs excruciating form

How much of this applies outside of mathematics? Most of it, if not all — but with a fundamental caveat that has become more and more apparent to me over the past few months.

Writing math is a remarkably well-defined activity and, if you have practiced it at any level, you will certainly have a feel for what Grothendieck is alluding to. Mathematical formalism is monstrously difficult to manipulate, to the point where it feels like torture. Yet its rigidity is unavoidable, as mathematical intuition can only develop through is confrontation with cold and hard logic.

In fact, forcing yourself to write things down rigorously, especially when you’re still confused, is an insanely effective life-hack routinely practiced by top mathematicians.

But outside of mathematics, writing means many different things.

My oldest son is entering primary school and learning to write. At his level, I can see that the simple act of forming a few letters requires intense focus.

For adults, we usually reserve the word writing for activities that go beyond the mere act of forming letters — or typing on a keyboard — and involve crafting original sentences and paragraphs. But even this definition remains loose, as I was recently reminded at my own expense.

After the English language edition of Mathematica was published, I became much more active on X. For all its flaws, I loved the reach and diversity, and it forced me to get better at the art of the aphorism.

Once you practice X for a while, especially if you experiment with viral content, the limitations of short form become pretty obvious. I started this Substack out of this frustration, as there were many important topics adjacent to my book that couldn’t be reduced to X threads.

If you had asked me six months ago, I would have told you that writing for Substack felt more similar to writing books than to writing for X. I’ve changed my mind on this.

After taking a three-month hiatus from Substack to complete the first draft version of my next book, I am amazed at how difficult it was. If X posts are short form and Substack is long form, then we need a different category for books — excruciating form.

To me, the experience of writing books feels very similar to writing math. This is probably because I operate with a similar mindset: starting with something that is fuzzy in my head, but feels important, and trying to “nail” it in a way that will withstand the test of time.

Math comes with a pre-existing framework that guarantees long-term validity (provided that ZFC is consistent — so far so good 😅). This is why writing math is always excruciating and always transformative, regardless of the format: it forces you to create new mental categories and stabilize their meaning in your head.

Outside of math, there is no pre-existing standard for quality writing. But you can create a makeshift standard by raising the stakes around your own production:

Will it make sense to people who know nothing about you?

Can it survive translation? Can it be read in Japan and Turkey, in Texas and India, in Kenya and Bulgaria?

Can gen Z offer it to their boomer grandparents, and vice-versa?

I don’t claim to have a clean methodology to answer these questions, and I am far from certain that my next book will pass the cut (at this point, I’ve identified several issues that need to be fixed).

But in the process of asking myself these questions, I did notice that they acted a bit like mathematical formalism: they were external constraints forcing me to be clearer and more articulate and, in the end, this reshaped my worldview.

There is something unique in the book publication process, in its archaism and solemnity, and especially in the fact that there is no way to “hot-fix” it once it is in press, no way to “quick-deploy” a follow-up piece that will respond to the objections prompted by the first one.

I’m a deep admirer of writers like Scott Alexander and Gwern who manage to thrive in long form while entirely skipping excruciating form.2 But, personally, I haven’t yet found a way of elevating my thought without resorting to it from time to time. This might be due to differences in personality, in cognitive style, or in the nature of what we’re trying to create.

To me, the main practical difference between long form and excruciating form comes down to this:

When writing a Substack post, I know beforehand what the post is about and what I want to say.

When writing a book, I have an intense but confused perception of what I want to say, but I’m initially incapable of articulating it, and the months-long process of trying and failing gradually makes me capable of writing it.

Here’s a more cynical way of looking at it: I can see how Claude 6 or ChatGPT-7 could be leveraged to fast-track the writing of this piece, but if I hadn’t written Mathematica in the first place, I would have no clue how to prompt for it.

Over the past few months, as I unplugged from X and Substack to focus on my next book, I was struck by how difficult it was for me — cognitively, emotionally, physically. It was much harder than anything else, much harder than I expected. I felt stupid and miserable the entire time, and I hated it. And yet — this ordeal changed me.

Whether you’re a reader or a writer, don’t give up yet on books. This is the No Free Lunch Theorem of cognitive development: at this point, we have no painless technology for collectively elevating our worldview.

I’m writing this piece on Serre’s 99th birthday — happy birthday to him!

It is to be noted, though, that both Scott Alexander and Gwern are avid book readers.

A very interesting read !

I think that writing makes me find the right equilibrium between the natural desire of my brain to create/diverge and the necessity to take into account all the contraints and chose an unique path.

Also do I use three different styles of writing :

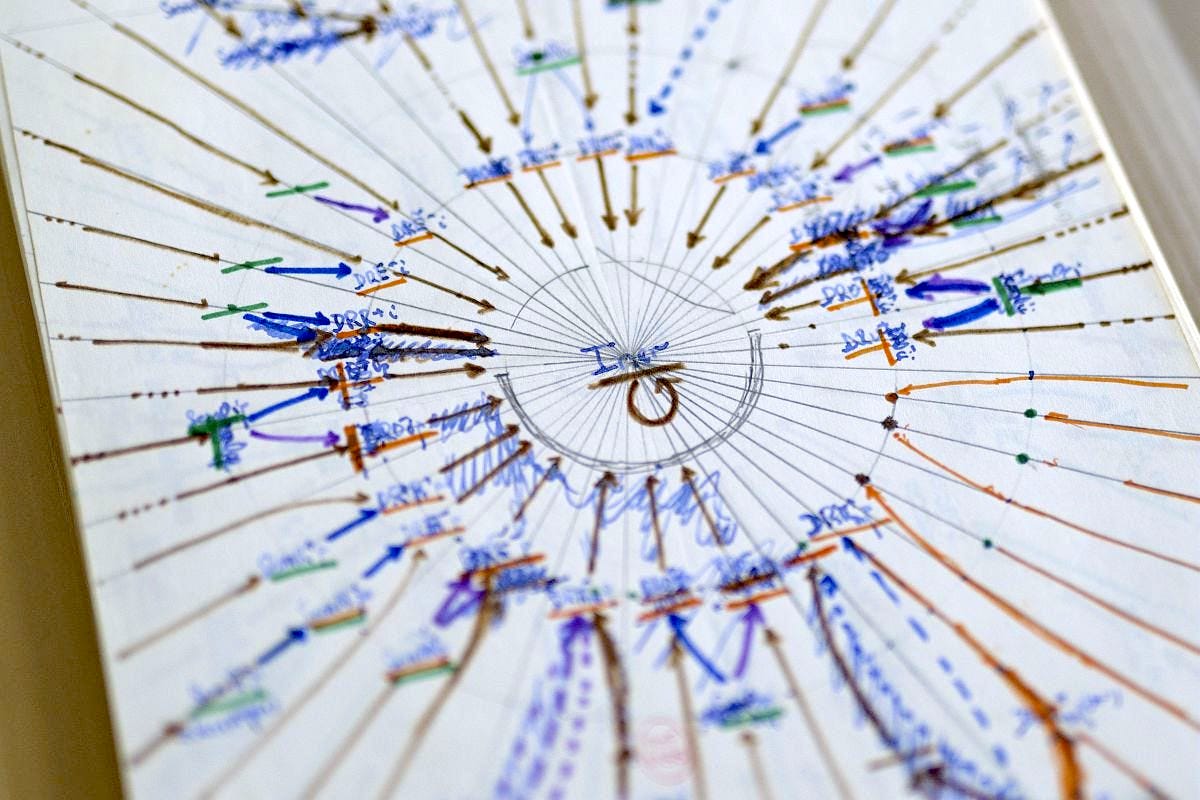

- unconscious writing on the margins/header/footers/whatever when thinking

- a messy notebook for iterations

- a clean notebook for fully constrained thinking where anything written should be almost definitive

Crazy P.S. : Maybe the closest non-written form of this excruciating process is serious conversations when clear ideas / concepts suddenly take shape

ribbit! this is pretty schizo! do we know if Grothendieck liked ducks? 🦆